Cutest Dog in the World Art Pieces That Has Sun Set

T hough he died in 1990, in many ways Keith Haring is withal live. His art is everywhere. At that place are Haring T-shirts, Haring shoes, Haring chairs. You can buy Haring baseball hats and badges and baby-carriers and playing cards and stickers and keyrings.

Keith Haring'southward work pops up all over the place – his radiant baby, the barking canis familiaris, the dancer, the three-eyed smiling confront. Simple, cheerful, upbeat, instantly recognisable. They make y'all smile and they work similar graffiti tags, small signifiers that say "Keith woz hither". Merely Haring did much more than provide beautiful cartoons. He was publicly minded. His art faced outwards. He wanted to inform, to start a chat, to question say-so and convention, to represent the oppressed. Those beautiful figures are political.

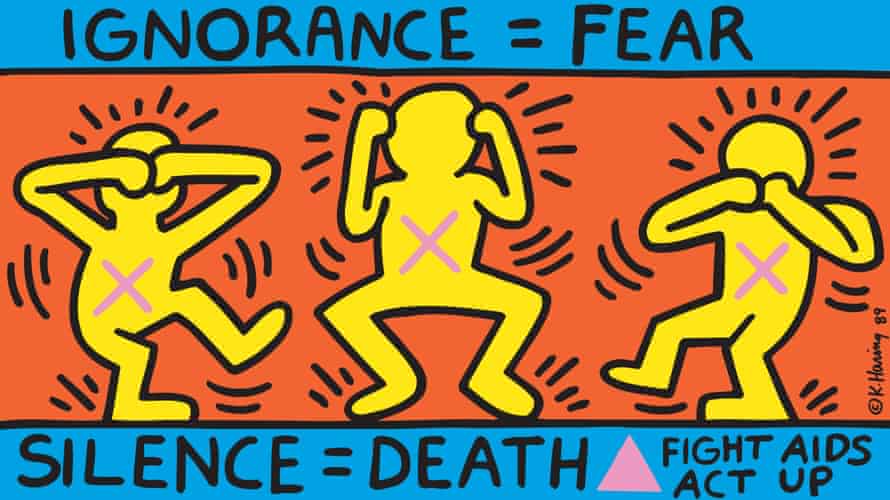

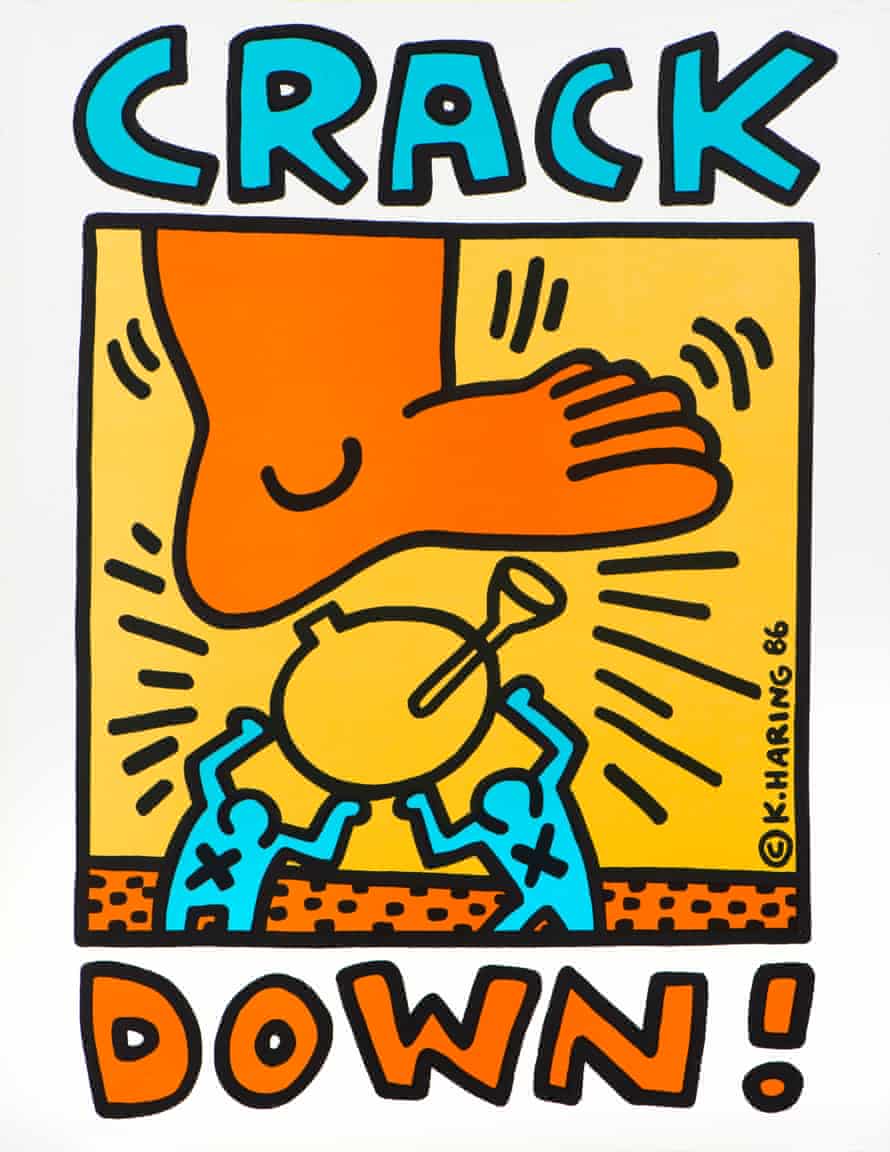

"Although his imagery is ubiquitous, he'due south actually an artist that has been disregarded," says Darren Pih, co-curator of this calendar month's major Keith Haring exhibition at Tate Liverpool. "People forget that back in the 1980s, he was talking near socially important issues: apartheid, Aids, environmentalism, how capitalism increases inequality – and he was using very accessible language."

Sometimes that language was direct, as in his Crack Is Wack mural (on 128th Street in New York), or the hundreds of specially designed posters he gave out at anti-nuclear and anti-apartheid rallies. Sometimes information technology was subtler: some of his subsequently works, when he knew he was dying, featured cleaved birds, daggers, nails, nooses, blood. Always, it was bonny, with an exuberance and joy that spoke to people of all ages, all backgrounds. That universal quality draws us to Haring's work – but tin lead some to call back that his fine art is superficial, and like shooting fish in a barrel to attain. It isn't.

"His line was amazing," says creative person Kenny Scharf, Haring's contemporary and friend, of the way Haring drew. "Keith was totally confident, that's one of the reasons why his art is so strong: the confidence in his line, the conviction, everything about it."

"He was unique," says Mare169, real name Carlos Rodriguez, a graffiti artist who worked with Haring in the 1980s. "The vernacular of his fine art was so appealing, with a quality of amusement. Just it was besides a tremendous, cute response to the activism of the time… the really unusual thing near Keith is that he felt he could be of service."

Haring lived and worked in New York from 1978 until his expiry, anile 31, from an Aids-related disease. In his final few years, he was invited all over the world to brand work, and if y'all want to see some existent-life Keith Haring art, you still can. In that location is a mural in Pisa, on the side of the church of Sant'Antonio, which he made in the last year of his life. There is one at the Blood-red public swimming puddle on Clarkson Street in Greenwich Village, New York, painted past Haring in one twenty-four hours in 1987. There is public work by Haring in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Antwerp, Berlin, Paris, Melbourne; on hospitals, at schools (often made with children), in an LGBT customs services centre.

Up until 2005, there was his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street in downtown New York. I went in that location in the 1990s, and information technology was an all-encompassing experience. The shop was tiny, with white walls and flooring covered in Haring's art. There was music playing and T-shirts hung up. It was playful and fun, with a social club vibe. I bought 2 badges.

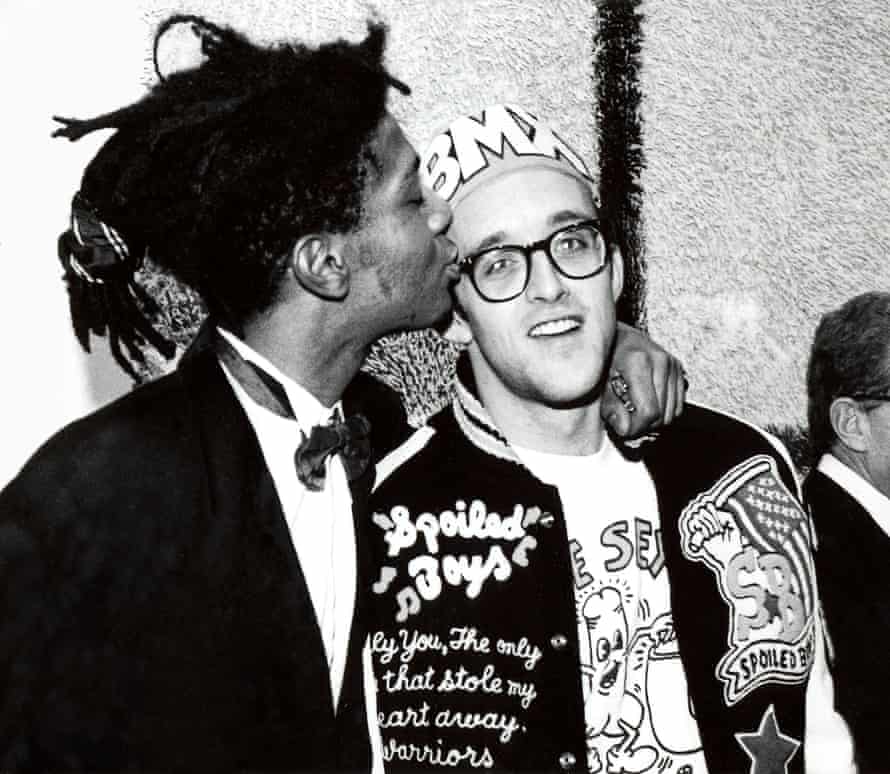

His work is timeless, only it is rooted in its fourth dimension. The Reaganite 1980s accept parallels with today, with an anti-immigration, anti-union, pro-guns, anti-ballgame, go-United states of america "entertainer" president in the White Firm. Back then, young artists reacted, shaking up the fine art establishment. A new post-Warhol crew that included Haring, Scharf and Jean-Michel Basquiat of a sudden emerged, making piece of work that referenced what was around them: clubbing, rap, street art, telly, high and low culture. They grabbed attention, shows and sales.

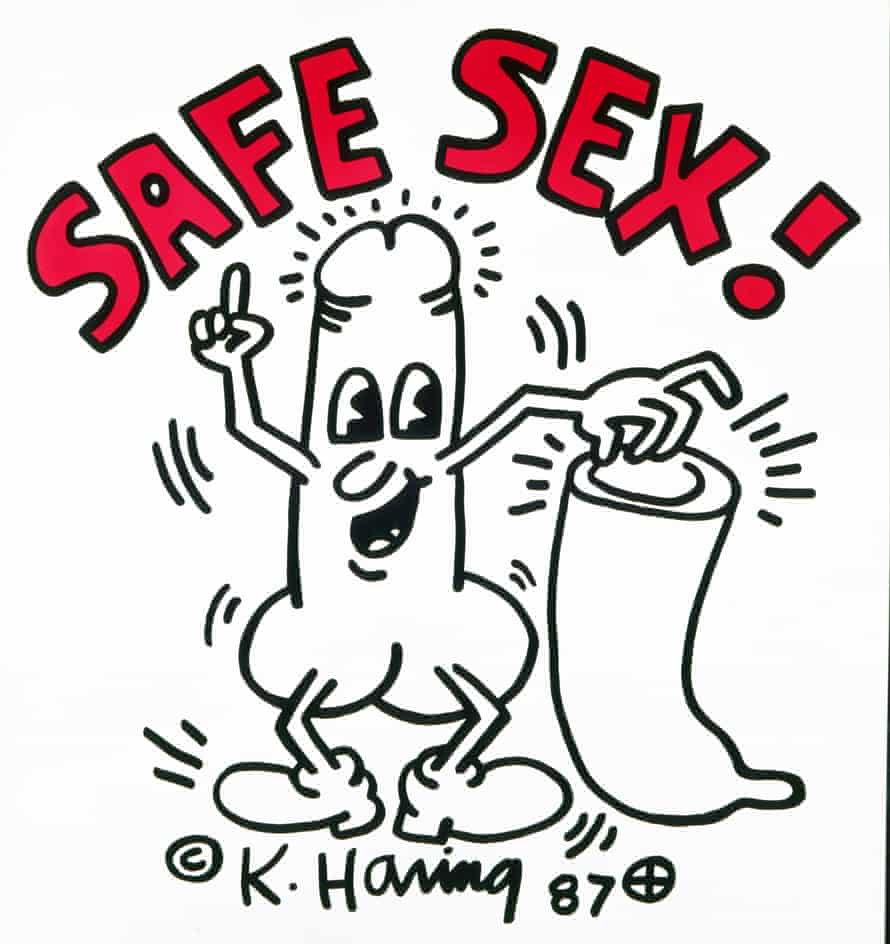

Merely art institutions, especially museums, didn't know how to react to these upstarts and their work. Neither did critics: some were supportive, many were snide (Time's Robert Hughes caricatured Haring as "Keith Boring"). There was a sense among the stuffy that these young artists were non to exist taken seriously, and Haring's likable painting way meant that his art, though loved by the public, was not "high" plenty for the elite. Plus, he collaborated with others too oftentimes; he was likewise commercial; he would keep banging on about politics and condom sex.

Today, though, Haring paintings sell for millions. In 2016, Sotheby's sold four Haring canvases, including the wonderful The Concluding Rainforest, which he painted in 1989 when he knew he was dying. The sale price was over £4m.

And there's a renewed interest in the artistic era in which Haring operated – that collaborative fourth dimension in New York where pop and rap and art met and mixed, a time that started in the mid-to-late 70s and ended, in essence, with a trio of deaths: first Warhol in 1987, so Basquiat in 1988 and finally, Haring, in February 1990. Terminal yr, the Beastie Boys, native New Yorkers, used their vastly entertaining memoir to paint a seductive picture of growing upward during that era. In 2017, there was a huge and highly successful Basquiat exhibition, in London; around the aforementioned fourth dimension, MoMA in New York put on a show based effectually Lodge 57, a pocket-sized nightclub where artists and musicians and performers would hang out in the late 70s and early 80s. The time in which these artists lived and worked seems so near, and yet and so far abroad. New York was still New York, but grubby, dangerous, abandoned, inexpensive. Fertile, angry, full of possibilities.

Keith Haring was born in May 1958. He grew up in a conventional family unit, led past a respectable man, in Kutztown, Pennsylvania. His dad, Allen, was a church-going, Nixon-supporting Republican, who drew cartoons in his spare time and encouraged his son to do the same. The Harings were loving, but Keith had a stiff sense that he was different. In his teenage years, he turned first to church, becoming what he would later call a "Jesus freak", and then, an acrid-dropping (Grateful) Deadhead and occasional runaway (he went to Bailiwick of jersey Shore for a summer when he was 17, against his parents' wishes).

After graduating from high schoolhouse, he enrolled in a Pittsburgh higher for illustrators, merely found it also limiting. He dropped out and hitchhiked across America with his girlfriend, funding the trip by selling his drawings. Soon after their return, his girlfriend said she was pregnant. Haring had just started sleeping with men. He knew he had to get out. "New York was the only identify to go," he said later on. He applied and got into the Schoolhouse of Visual Arts, on Eastward 23rd Street. Other students included Samantha McEwen and Kenny Scharf.

At their very first lesson, a drawing class, remembers McEwen, Haring "dragged his chair all the way across the room" to sit down opposite her, so that he could draw her, and her him. She thinks it was because she looked different to the other course members, considering she was English language, with mad curly hair, dressed in secondhand clothes. They had an instant rapport, she recalls. "He was so mannerly and engaged. He really listened."

Dissimilar most xx-year-olds, Haring was clearheaded and motivated; he knew what he wanted to practice and he used his time well. "He would move into any space that was available," says McEwen.

Scharf recalls that Haring "ever took the initiative, he located any avenues that were available in a smart fashion. He actually had it together."

When he spotted an unused room in SVA, Haring found some three-metre wide paper, put information technology on the floor of the room, where information technology fitted exactly, and started painting in at that place. He brought in his record player and painted to Devo, timing the castor-strokes to the music, stopping when the track stopped. Scharf met him for the first time here, as Haring was literally painting himself into a corner.

"A lot of other artists were jealous, like: 'Oh, you lot get to do this room just for yourself, how come up y'all go to do that?'" remembers Scharf. "And information technology was like: 'Well, you didn't ask!'" The outgoing, charismatic Scharf was already known for dragging in debris off the streets into SVA to glue together and paint. He and Haring became instant friends.

Haring was warm and open, only focused – "always learning" says McEwen – and more opinionated than most of his contemporaries. A compulsive diarist – he believed recording his work was part of his practice – Haring wrote later that he came to SVA "prepared to aggressively get things from the schoolhouse, instead of expecting the school to give them to me". He hung the Devo paintings on the college walls without permission, and from that, got himself an exhibition.

Though Haring was confident in his drawing, he was also interested in words, and experimented a lot with poems, likewise as new technology like Xerox and video cameras. Some of his outset New York works were cut-ups of tabloid covers ("Ronald Reagan Accused of Goggle box Star Decease"), and when, at a Canal Street sign shop, he found a handbag of 13 messages, he used them to make a sort of restricted poetry: "art art boys sin as if no if no art lick fat boys". He used them as the basis of videos, created Xeroxed, Warhol-esque posters and would read the "art boys" poems at Social club 57. For a while, in 1979, he wore a black beret and called himself a terrorist poet.

The then new Club 57 was in a Polish church at 57 St Marking'due south Place. Haring, Scharf and some other SVA educatee called John Sex stumbled across it by mistake; they liked the jukebox and put a track on. Ann Magnuson, who ran the gild, came out from behind the bar and started go-go dancing with them. Magnuson got her new friends to do one-night fine art shows at the club, "and it kept tumbling like that", says Scharf. "Every dark, performances, art shows, happenings." Unlike the well-established punk venue CBGB, or the Mudd Guild, both of which were cool ("heroin-y"), or the loftier-stop celeb-station that was Studio 54, Club 57 was modest, airheaded – "uncool," says McEwen – and very sexually free. Everyone was sleeping with everyone else. The chosen drugs were booze and hallucinogens. Haring loved Society 57's attitude, which was less nightclub and more playroom: he staged spontaneous art shows, read his poems, joined in with big Twister parties. He did performances with a Goggle box on his head, speaking through the screen.

Haring was interested in art that talked to people. After just one month at SVA, he wrote a manifesto-cum-self-definition that included the words: "The public has a correct to art/The public is being ignored by nearly contemporary artists/Art is for everybody." As far as Haring was concerned, it was the viewer that created the meaning and reality of the artwork. So he wanted to proceeds as many viewers as possible. ("As graffiti artists say," says Rodriguez, "he wanted eyeballs.")

McEwen remembers him painting abstract images on the footing in the loading bay of SVA. Lots of passersby stopped to talk, to tell him what they idea. "1 would say it reminded them of fighting in world war two, some other said they could come across animals in in that location," she says. "He thrived on that interaction and I think it pushed him to accept his art out on to the streets."

She as well recalls Haring'due south show at an abandoned schoolhouse turned DIY art venue, PS122, in 1980. He had turned from poetry back to art, and at the evidence, he debuted the style that became his signature. He drew pictures of flying saucers shooting out light-rays, of penises existence worshipped by crowds of people, of a baby that shone like a star. "Information technology was and so arresting," she said. "Immediate."

Street art was flourishing in New York. Tagging and graffiti art was part of the emerging hip-hop scene, which was by and large based uptown, in Harlem and the Bronx, but moved to the Lower East Side one time rappers and taggers similar Fab Five Freddy started mingling with downtown artists. Jean-Michel Basquiat, whose own SAMO tag began as a sort of on-wall manifesto poesy, wasn't a student at SVA, but would visit the college, invited past Scharf.

Though Haring, Basquiat and Scharf were very different artists, all three were interested in making work exterior galleries. Haring started tagging – he drew his tag, the radiant baby, adjacent to existing graffiti, never over the top – and Basquiat was already doing so. All three were as well interested in the risk and magic of making work without preparatory drawings, and Haring was the king of this. Lenore and Herb Schorr, collectors of both Basquiat and Haring, recall his ability to make full whatever space he needed to.

"He was a phenomenon," says Lenore. "He would just get upwardly in front of a wall and correct from his caput, no cartoon, he would first working. It was unreal, his agreement. He saw the space and he filled information technology and it was beautiful and it was balanced, it had a rhythm."

"It was more than that," says Tony Shafrazi, who became Haring'south dealer. Being out and about cartoon on walls led Haring to look at the streets differently. He noticed the pocket-sized advertising spaces at subway stations. Whenever an old advertising was removed, but earlier the new one was put up, the space was covered in black newspaper. Haring decided to draw on these blank canvases in chalk.

"He was unbelievably quick," says Shafrazi. "I went with him on a couple of the trips and he would spot a space, sprint out and information technology would be washed in minutes. He would go upwards one line, come up dorsum down; he went all over Manhattan similar that, roofing the place."

An SVA friend, the lensman Tseng Kwong Chi, would come past a few hours after and take pictures of the chalk drawings before they were covered over or stolen. Haring was arrested a few times for this, but it just added to the street glamour (CBS's Sunday Morning did a slice on him, complete with user-friendly cop handcuffing him). People would stop and chat to him while he drew, and he fabricated badges and handed them out. Robin Williams had one. And then did Diane Keaton.

At that time, Scharf and Haring shared an apartment, a huge two-storey loft well-nigh Bryant Park, filled with both of their work. But it quickly became tricky for Scharf, considering Keith's work was becoming popular. Collectors came up to their apartment to buy a Haring and walked straight by Scharf's piece of work. "Information technology caused Kenny a lot of angst," remembers McEwen.

"We all had ambitions of moving up, getting a bigger audience and money," says Scharf, "simply when it happens, things change. It isn't and then fun and uncomplicated as it was when nosotros were each other'south audience. There'southward other people'southward take on you, you're taken more seriously, then they're more critical, then there'southward jealousy. Before, you had a focal bespeak of getting out there and creating, and and then all of a sudden y'all have to deal with this motorcar that you wanted to be involved in, but that you didn't know annihilation about." Before long after, Haring decided he needed a dealer, and chose Shafrazi.

In 1981, Haring moved in with McEwen, into her Broome Street railroad apartment, where at that place was no corridor, and each room led into another. At the get-go, McEwen's rooms were the kitchen and a bedroom, but that changed when Keith became romantically involved with a DJ called Juan Dubose, "and it became clear that Juan needed access to the kitchen," says McEwen.

Juan's contribution is underestimated," she says. "He did all the cooking for Keith, he sort of kept firm so that Keith could work." With Dubose moving in, McEwen swapped rooms, only then she had to walk through Haring and Dubose's bedroom to become to the kitchen. And then Haring bought a tent. "But a perfect-sized tent that was his and Juan's bed," says McEwen. "I came back one day and there it was. With the Boob tube right up against the door to the tent and so they could picket it."

Though neither was completely monogamous, Haring and Dubose were together for several years. They loved to dance, and became regulars at the Paradise Garage, where Larry Levan DJed. Haring adored the exhilaration and community at the club: when he became successful and had to travel around the world for his piece of work, he would organise his schedule so that he would leave direct after a Saturday night at the Garage or return just before, "so that I didn't miss any of my Garage time". Dancing was immensely important to him, as were the "beautiful boys" of the Garage, who were generally black and Latino. Haring was attracted to not-white men. "I'm sure inside I'm not white," he one time wrote.

In 1982, Shafrazi put on a solo Haring show. It was a huge success. Important art collectors mingled with Haring'due south downtown friends, plus graffiti artists and hip-hop DJs. From there, things really took off. Haring met Warhol and they became close. He went for dinner at Yoko Ono'southward, he hung out with David Bowie, Iggy Pop, William Burroughs, Robert Mapplethorpe. He already knew Madonna, from clubbing at Danceteria. He went to her wedding, and took Warhol as his invitee.

Past 1984, Haring couldn't do the subway paintings whatever more, because people were stealing them equally soon equally they were upwardly and putting them up for sale. Fake Harings started springing upward; his style was much imitated, especially in Japan. In 1986, he gear up his Pop Shop on Lafayette Street. He wanted the public to be able to access his real work, not merely those with enough money to be able to buy ane of his paintings. Pop culture accepted his art long earlier the institution did. For Haring, the Pop Shop "was the ultimate in cutting them [the art establishment] out of the pic".

Scharf remembers this. "Keith was crucified for it," he says. "The art globe likes to think: 'Oh, if yous're doing things in a mass commercial way, you're dumbing it downwardly for the masses.' Well, no. Nosotros're not dumbing things down, nosotros're bringing people up. But the art earth doesn't want to see people coming upwardly."

Haring frequently spoke eloquently about the notion of "selling out". He turned down many offers of lucrative piece of work: to license his fine art in Tokyo, to run a Macy'due south boutique, to pigment a Hall & Oates album cover, to annunciate Kraft cheese and Dodge trucks. He accustomed some, like Swatch and Absolut: those that offered a claiming. "Ever since there accept been people waiting to buy things, I've known that if I wanted to make things people would want, I could do it hands," he said. "Equally soon every bit yous let that bear upon yous, you've lost everything."

And he continued to work with graffiti artists, though he merely went out tagging with them in one case; he felt stupid as the older white guy, similar a chaperone. He didn't call himself a graffiti artist – in an Interview piece, he described what he did as cartoon, rather than graffiti – but the media didn't mind. He talked to Rodriguez about information technology. "Keith and I often discussed this," he says. "I would say to him, You're not a graffiti creative person. And he would say: 'Oh, information technology'due south the media, information technology's how they write it.' Just we both knew that he was playing along with it, because it helped requite rise to his success. The thing that people don't know is that his success also elevated us too. There was this mutual understanding and agreement that he was really making headway for a lot of people. He was making street fine art acceptable."

Dancer Bill T Jones believes that Keith tried to raise consciousness in general. "Anybody knew his sexuality, he was very out, which was important," he says. "And he would try and represent the young, underserved black and brown people of the streets, like the Central Park Five. The art world claimed to not know virtually such things – and its passivity, its silence was political – but because of the people he associated with, Keith was pulled into these issues."

Jones worked with Haring on a number of occasions, including in the UK in 1983. For a testify at the Robert Fraser gallery, Haring decided he would paint Jones'due south naked body and have Tseng take photographs. The painting took iv-and-a-one-half hours, and when he was done, the press were invited in to do interviews. Jones remembers the whole upshot with affection, calling it both "innocent" and "brazen". "That torso-painting gave me power," he says. "Information technology fabricated one feel transformed, into a heightened consciousness, a special condition, I was a moving sculpture." After this, Haring painted Grace Jones.

Haring's horizons were expanding. He painted on the Berlin Wall, he worked with MTV. He was immensely popular: in 1986, he was the subject of more than 100 newspaper articles. But in the mid-1980s, every bit he was flying loftier with his career, back in New York, the carefree surroundings began to change.

Aids swept through New York like a burn down, "like world state of war 2," recalls Jones, whose dance and life partner Arnie Zane died of Aids-related lymphoma in 1988. "An entire generation was killed, it decimated a whole course of persons, the homosexual, creative people."

McEwen got meaning around this time and was required to take an HIV test. She had to take her blood sample to an abandoned car park, to a box-similar structure that was set upwards away from people, and post the sample through a slot. Everyone was petrified of catching this new and terrible illness; no one knew quite how it was spreading. But spreading it was, and people were dying.

"People got sick and they'd die in two weeks," says Scharf. "Recently, I went to a friend'south photography show and looked at a photo of united states all, and everyone is no longer hither and they've been gone 30 years."

"You had a kid, and you lot'd look effectually for who could be godfather," says McEwen, "and there was nobody left."

Haring knew he was at gamble – Dubose had been diagnosed HIV-positive. His friends were dying, including Bobby Breslau, a mentor who worked at Popular Store. Haring was badly affected by Bobby'south suffering, merely was accepting of his own fate. He wrote about the possibility in his journals in March 1987.

"I am quite aware that I have or will have Aids," he wrote. "The symptoms already be… my days are numbered. Important to do as much as possible as speedily as possible. Piece of work IS ALL I Have AND ART IS MORE IMPORTANT THAN LIFE. I e'er knew, since I was immature, that I would die young, Only I thought it would be FAST (an accident), not a illness… time will tell but I am not scared. I live every solar day as if it were the last. I Dearest LIFE. I love babies and children and some people, about people, well maybe not most. But a lot of people…"

In 1989, the year before his decease, Haring did iv shows. He set up the Keith Haring Foundation, which still exists today, working to support underprivileged children and HIV charities. And he did an interview with Rolling Stone.

He said: "No affair how long you work, it's ever going to finish onetime. And there's always going to be things left undone… part of the reason that I'yard not having problem facing the reality of death is that information technology'southward not a limitation, in a way. Information technology could have happened any fourth dimension, and it is going to happen erstwhile. If y'all live your life co-ordinate to that, death is irrelevant. Everything I'm doing right now is exactly what I desire to do."

Haring worked right up until 2 months earlier he died. Scharf was at his side when he was very ill. Haring was agitated, twitchy, with his eyes shut, and Scharf held him. "I said: 'Y'all can relax. Everything you lot've done is going to keep going. Yous're going to continue.' And I felt him relax. I meant it. He started something actually big, and I will always honour his legacy."

Haring died on 16 February 1990. During his lifetime, he had most 50 one-human being shows. He painted 45 murals. Since his death, his foundation has supported hundreds of youth, customs, art, LBGT, rubber sex and planned-parenthood projects. His work is held by MoMA, the Whitney, the LA County Museum of Art, the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh. And many, many people own a Keith Haring bluecoat.

The Keith Haring exhibition is at Tate Liverpool, 14 June-x November

mcclellankinge1987.blogspot.com

Source: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jun/02/public-has-right-to-art-keith-haring-tate-liverpool-exhibition

0 Response to "Cutest Dog in the World Art Pieces That Has Sun Set"

Post a Comment